Disclaimer: Don’t try this at home! We’re professional (?) volcanologists working with expert mountaineers. For up to date advice on Nevados de Chillán, and any other volcanoes we visit check out the website and Facebook page of Sernageomin. Always follow their advice, and always respect the exclusion zone.

The safest place to be in an eruption?

Nevados de Chillán was our first stop in the Southern Volcanic Zone (SVZ) after crossing the Pampean Gap, and we were all looking forward to getting back to work after such a long journey. Additionally, our clothes had almost lost the odour of sulphur, and we risked having our volcanologist membership cards revoked. Much about the SVZ stood out in stark contrast to the North. The green, wet landscape of the SVZ hosts massive, prominent mountains, with their bases at lower elevations. As the physical geography changes southwards, so does the human. We had the mining industry to thank for our 4x4 tracks in the North – down here it would be the tourist industry, which has built roads, chair lifts and service tracks to reach ski pistes and hot springs on the volcano flanks.

Nevados de Chillán was a case in point, with its steep ski slopes and enticing hot springs. We stayed at the foot of the volcano in the resort town of Las Trancas, nestled at the end of a long, forested mountain valley flanked by steep crags. The bustle of tourists came as a shock after the remote quietude of Lastarria. Our diet improved dramatically – no more boiled frankfurters and instant mash seasoned by the dusty desert winds. In fact, we slept indoors, in great comfort, thanks to our sponsors Cabañas Basecamp. We now dined on finest Chillán longaniza and had a choice of delicious fresh empanadas, which brought new dilemmas– frito or horno? Pino or queso? These decisions can split the most cohesive teams. However, the easy living was not to last and we would soon be bouncing up some of the steepest 4x4 tracks we had yet to encounter, as well as donning our crampons and ice axes for the first time. In fact, Nevados de Chillán proved so interesting we would be back again and again.

Nevados de Chillán is a very active composite andesitic stratovolcano, and consists of three distinct cones coalesced to form a north west to south east trending ridge. Three days before our first visit, a phreatic eruption blasted a new crater into the side of Volcan Chillán Nuevo, the central peak. One of our main objectives is to identify the provenance of the volatiles Andean volcanoes emit – how much is simply ground water and air circulating in hydrothermal systems and how much is freshly emitted from bodies of magma at depth. At Nevados de Chillán we had the rare chance to answer this question for a volcano undergoing explosive activity.

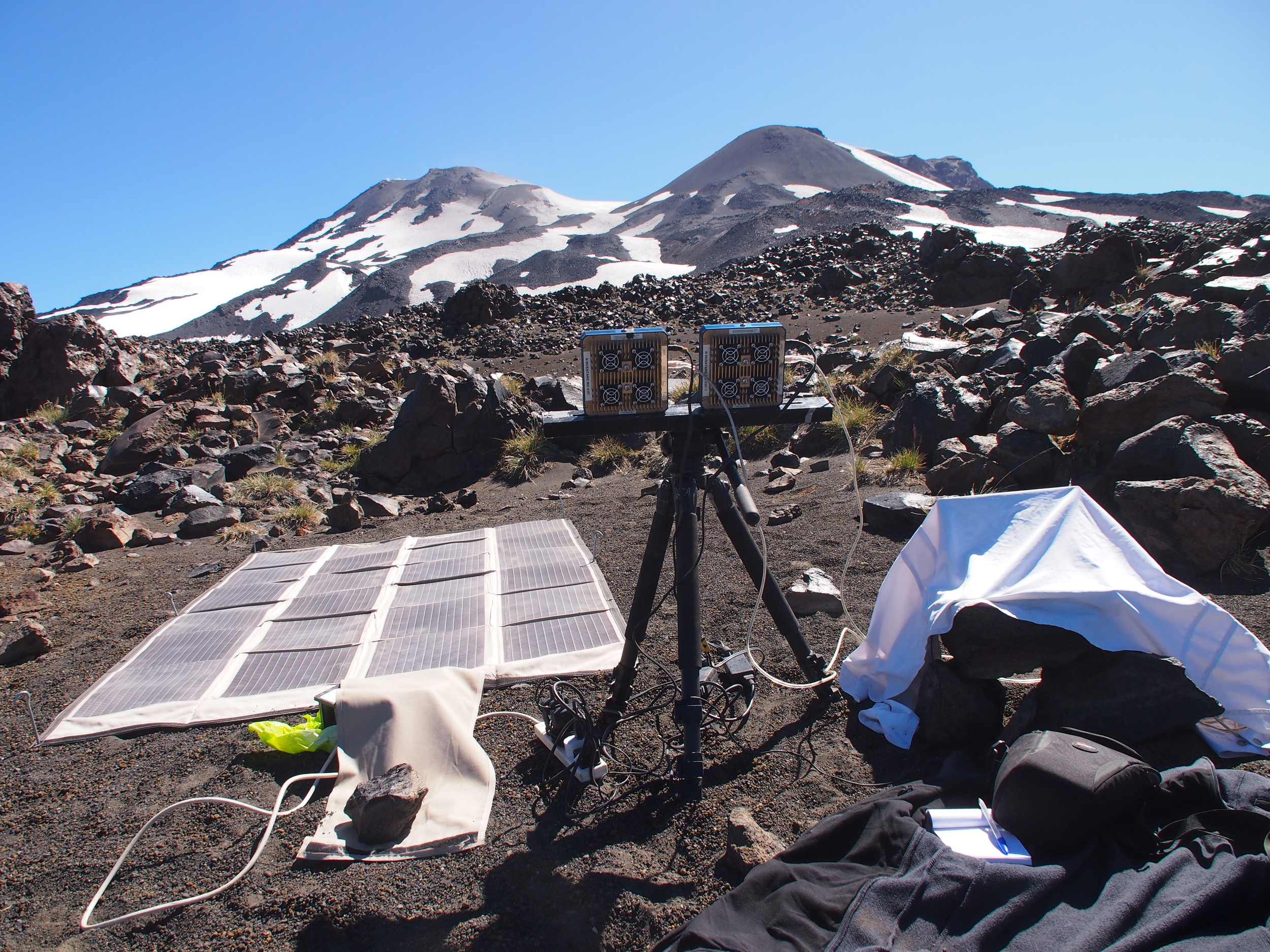

We teamed up with new friends from Socorro Andino, René, Monchy and Corinne, and the owner of the ski resort kindly agreed to activate the chairlift to take us a good way towards the summit. Recovering from his first chair lift ride, Talfan set up the ultraviolet remote sensing station at the head of the chair lift, while the rest of the team donned their crampons and pushed on. Walking with crampons on ice for the first time after sliding around on boots is an amazing experience – it turns your soles into ‘ice velcro’, and you can walk almost anywhere. We say almost anywhere, because you can’t walk up crevasses, but we avoided those with the help of expert mountaineers Renée and Monchy. While Talfan set up the cameras and spectrometers, the summit team made their way cautiously towards the source of the new activity. This was hidden from view behind the summit, and the team were unsure of exactly what they would find…

We use ultraviolet light to measure the presence of SO2 in volcanic plumes because we can - sulphur dioxide is the ‘Goldilocks’ gas for volcano remote sensing. There is very little background SO2 in the atmosphere compared to volcanic plumes, so we don’t have to worry about whether the SO2 we measure comes from volcanoes or another source. Sulphur dioxide is also easily identifiable as few other gasses absorb at the same wavelengths – it has a unique 'fingerprint'. Additionally, the pervasive scattering of sunlight in the ultraviolet means that during the day there is usually enough light passing through the plume in any direction to make a good measurement – the acquisition geometry isn't dictated by our need to boost the signal using directed sources of intense radiation, like direct sunlight, a heat lamp or hot lava. By comparing the signal at wavelengths where SO2 absorbs light with those where it doesn't, we estimate the amount of the gas in the plume. We then combine this with estimates of the speed at which the plume is moving to get the flux, or the rate at which the volcano is emitting SO2. Because we need a good view of the plume to do this, we set up our ultraviolet remote sensing instruments a few kilometres away, nice and safe. All we need then is an estimate of the ratio of the other gasses to Sulphur dioxide and we can get the fluxes for all gases of interest. And that, in a nutshell, is all we do. Apart from isotopes, but that’s a whole blog post in itself.

Easy!

You might think.

But most of the other gasses are not so co-operative. Either the atmosphere is already full of them, or they are emitted in very small amounts, or they absorb light in awkward parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. Usually, we need to go to the plume and get a sample. And as the summit team crested the mountain, and saw the steaming source of the recent emissions, they realised something, or someone, was going to have to go down there:

A newborn crater -- shown 4 days old. The slope is steeper than it looks!

Previously, on Trail by Fire, we’ve used a range of devices to get our sampling instruments to the plume. But here, our sampling quadcopter was temporarily grounded, and even the mighty STICK wasn't going to reach. It was time to get out the big guns: YVES (Yvo Volcano Exploration System). YVES is autonomous, adaptive, knows no fear, and runs on granola bars.

Under the eyes of our nervous team Yves was belayed down the flank of the volcano to the steaming pit and waited an an agonising few minutes while the MultiGas system buzzed away, pumping the precious gas through its array of sensors. Eventually we had enough measurements to get the ratios of the various gasses to each other and Yves clambered back up, mission accomplished.

We returned to Nevados de Chillan a few weeks later and found the situation had changed. Explosions had continued and became much more frequent, so there was no prospect of approaching the new craters on foot. An exclusion zone now extended two kilometers around the summit, placing the vents beyond the range of our quadcopters, let alone the mighty STICK. We fell back to UV remote sensing from a safe distance, this time taking our mobile volcano observatory up the insanely steep ski piste service tracks, an endless series of switchbacks snaking up the boulder strewn slope, and were treated to a spectacular series of eruptions over the next few days. The explosions were eerily gentle due to their silence and the slow billowing of their plumes, but this was largely a function of distance – up close, these events are dangerous. After a few days measurements, we packed up, and said goodbye to new friends René, Corinne, Monchy, Gordon, Ponda and Flash.

At a conceptual level, Earth scientists know that plate tectonics is about big things, but it's rare to be able to experience this viscerally. Usually on field trips, we see a fault scarp here and a volcano there and have to put the larger features together in our imaginations. One of the great privileges of being a part of Trail by Fire has been simply driving along the Andean volcanic zones, day by day, week by week, getting a feel for just how big they are. And they feel big, a feeling that can't be conveyed by textbook diagrams, or satellite images. It's been an enlightening and humbling experience. The view from the top of Nevados de Chillán was spectacular, but we could still only just see to our next target volcano. Far away across the snow capped peaks was the tell tale brown smudge of volcanic plume hanging on the horizon, that could only have been put there by a volcano much more active than Nevados de Chillán. It could only be one volcano: Copahue. But would we make it there?

Copahue

Picture credits: Trail By Fire, Monchy Zapata Vergara, René Gonzalo Cardenas Bravo